Bartkey reflects on the lessons of crime journalism

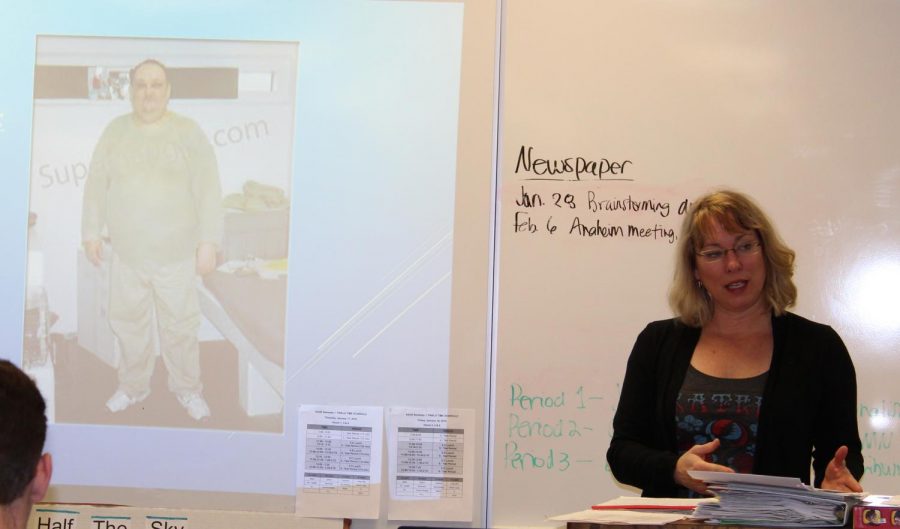

Julie Bartkey presents key points of her career with first hour newspaper students.

January 21, 2019

Standing at the head of the classroom, she stood tall with an inviting smile on her face, upholding herself with impeccable professionalism. She was an award-winning journalist, with an Emmy and multiple associated press awards to her name. Though she had a sophisticated demeanor, her seasoned career exposed her to some of the most evil crimes in existence, and to this day, she can recall the moment evil looked her in the eye.

Julie Bartkey, formerly known as Julie Klesh, was a journalist up until around 2016. Much of her career was spent in Great Falls, Mont. In 2001, she reported on a horrific case of child molestation, with possible cannibalism and murder. This was the case of Nathan Bar-Jonah, a story that made national headlines for its gruesome extremity.

Becoming a crime journalist

Bartkey’s path to journalism was uncertain at first. She received a degree in social work from University of Wisconsin River Falls (UWRF),but while working in her internship, she decided it wasn’t the right fit for her. The Kansas City Chiefs, a football team from Kansas City, Mo., was training at UWRF, and one of Bartkey’s friends was interning for sports journalism with the team. Bartkey then spoke with the head of the journalism department to double major in social work and journalism, started working on internships in the Twin Cities, and began a career as a sports journalist.

“I have this philosophy that if you can work a sixty hour week covering something, and not get paid for it, and still love it, it’s probably the career for you,” Bartkey said.

After college, Bartkey moved to Great Falls, Mont., a small city in the western part of the state. Here, she expected to become the Monday night football sideline reporter for a Great Falls news station, but she quickly found that there was little opportunity in sports coverage in Great Falls. This led her to stray away from sports reporting, and she eventually found herself in crime journalism.

Working in crime journalism is “A lot of relationship building with the officers, and pretty fascinating cases,” Bartkey said.

Though Bartkey is no longer working in journalism, she values the industry and what it has taught her. Though she felt that it helped her learn and push herself, it presented challenging cases, such as the Bar-Jonah case.

“Journalism is a fantastic career because while you have these set parameters in terms of set expectations for deadlines… or expectations from an assignment editor or your editor in terms of what you’re going to cover, every day is just different, and every day is an opportunity to learn something new. But, with that, comes the unknown,” Bartkey said.

The Bar-Jonah case

Great Falls has a relatively small market in terms of news, according to Bartkey, but Bartkey had the opportunity to report on a crime story that made national headlines, the case of Nathaniel Bar-Jonah. Bar-Jonah, prior to his crimes in Great Falls, had served time in the Massachusetts Institution for the Criminally Insane and Violent Offenders. He was grandfathered in before Megan’s Law, which states when perpetrators must register as tier-three sex offenders, so Bar-Jonah did not have to register. He then moved to Great Falls.

“Right before I moved there, this little boy, Zachary Ramsay, disappeared on his way to school,” Bartkey explained.

Through the case, it was discovered that Ramsay was kidnapped by Bar-Jonah. He was likely murdered, but no murder charges were put on Bar-Jonah. During the investigation of the case, a journal kept by Bar-Jonah was found, where he wrote recipes for “little boy stew,” presenting the possibility of cannibalism.

It was likely that Bar-Jonah served dishes containing human remains to his neighbors, Bartkey said.

Before the Zachary Ramsay disappearance surfaced, Bar-Jonah was arrested for impersonating a police officer near an elementary school in Montana. It was clear that he was looking for another child. Police had been keeping watch over him, and they suspected he was associated with Ramsey’s disappearance. Officer John Cameron then got a search warrant, went to Bar-Jonah’s home, and found enough evidence to charge him. He was then sentenced to 130 years in prison and died there.

Ramsey was not the only victim on Bar-Jonah’s crimes. When he was in prison, four more boys came forward with testimonies of sexual molestation, which led him to be charged with four counts of sexual assault and assault.

The hardest time to report on the Bar-Jonah case was “when one of the little boys was on the stand and he was explaining what had been done to him… it was really hard because I was a parent,” Bartkey explained.

The effect on Bartkey

Working on the extreme Bar-Jonah story has affected Bartkey on a personal level. Though she stayed grounded in the process and remained completely unbiased in her documentation of it, she left the process with a multitude of new understandings. The experience had opened her eyes to the nature of crime and the good/evil dynamic in human beings.

From the Bar-Jonah case, Bartkey learned “that people are inherently good, but when they’re not, they’re really not… some really good people might do some really stupid things and land them in jail, but if you’re evil, you’re probably really evil. There is not a lot of middle road,” Bartkey said.

Since she was a young mother at the time, the experience of the Bar-Jonah case left Bartkey with a new outlook on parenting. Her son was two years old at the time of the Bar-Jonah case. Though one might assume a parent might become more protective and paranoid while reporting on such a gruesome crime story, Bartkey’s direct experience with it led her to recognize the rarity of serious crimes.

“I am so not a hover-mother. I think I realized that crimes in general [are] more of an anomaly than a lot of people think. People tend to hear the worst case scenario and assume that might happen to their own families, I take the other way around. It’s the worst case scenario, it’s making the news because it’s the worst case scenario, and things like that rarely happen to our own families. So, if anything, [reporting on the Bar-Jonah case] has made me a lot more laid-back in my personal life,” Bartkey explained.

One of the most chilling experiences Bartkey can recall from the Bar-Jonah case was the moment she made eye contact with Bar-Jonah. She described his eyes, one brown and one blue, to be completely dead, and his face cold. Just by looking at him in the eye, she could immediately sense how truly evil he was.

“When you look in the face of someone who really is the devil, you understand that evil does exist, and I carry that with me still,” Bartkey said.

Bartkey’s success in crime journalism has not only won her awards, but a refined perspective on crime, parenting, journalism, human nature, and life itself. “I came out of it impacted but happier, and more grateful, and more grateful for that career, and grateful for the things I learned from that career. Really, the most important part was that I was able to really separate and look more broadly at society’s landscape and realize that the dark things might cover them, [but] the reason you’re covering them is because they don’t happen all the time. Once you can put things in a different perspective, you can move forward with your own life. I got a very strong sense of gratitude. It was a great career, I covered some very fascinating things. But when it was time to put it aside, it was time to put it aside, and I can talk about it here and not be very emotional,” Bartkey explained.