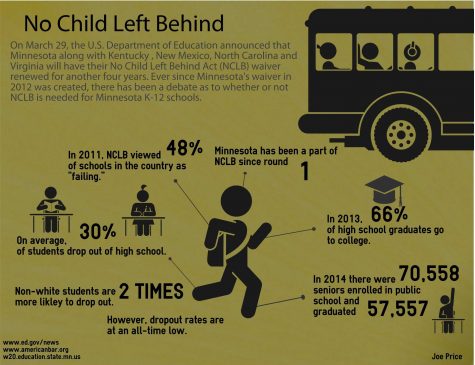

No Child Left Behind leaves minorities deserted

When it comes to educational standards, lawmakers can agree there are only so many ways to judge a school’s performance. There is a strong division, however, between how much standardized testing should influence a school’s performance versus individual teacher review. Minnesota lawmakers in particular are struggling with the current No Child Left Behind law, which requires a school to perform at a certain level on Minnesota Comprehensive Assessments or put students in remedial classes. While standardized testing is great for determining overall strengths and weaknesses, it lacks the ability to determine a student’s true potential and does not take into account variables such as home life or inability to perform at a high level.

Special education students and teachers in particular do not favor well from standardized testing, because they receive the same test expectations as the average student who has no disabilities. If special education teachers do not receive the required score from their students, school districts are sometimes forced to fire the teachers because of their students’ “poor performance” on the tests. Most Minnesota school districts also require special education students to submit various legal forms in order to take a different MCA test, and even then, the test does not always suit the individual needs of the students.

It is not just special education students who feel the pain of standardized testing, however. According to the Education Resource Information Center, Minnesota’s statewide graduation policy involves a series of several MCA tests, of which a student must obtain a cumulative score of 24 out of 48 possible points, which averages to about 70 percent correct on each test. For most white Minnesota students, that average is not a problem, with an average of 80 percent correct across Minnesota, but for minority students it is a much different story. Based on analysis from the first MCA in 1997 to now, African-American students in particular have scored an average of 25-35 percent lower than white students on each MCA, which calls into question the effectiveness of such a test.

Standardized testing, while clearly proving that Common Core programs and the No Child Left Behind law do not necessarily work for all students, has given Minnesota lawmakers some insight into other programs that more effectively deal with the unbalance of educational standards. Educational analysts have found that standardized tests can never truly be taken away completely because they do offer a general analysis of a district, but high stakes standardized tests are definitely not the best way to assess individuals. To find a common ground, a program called The Nation’s Report Card has created mini-tests which measure a school’s individual progress over time, rather than one student’s score on a test. Some schools are also adapting the No Child Left Behind law to include short online games, which measure a student’s ability to react to a computer’s decisions. While it is still in the test phase of development, schools have already found these games to be fantastic in determining a student’s full capabilities.

In short, the current No Child Left Behind law has made progress in more accurately measuring a student’s progress, but ironically leaves behind the students on the fringes of educational development such as special education students, minorities and students in poorer regions of Minnesota. While the law should not be cut entirely, there are plenty of alternative options for determining a school’s performance level, and these options should be used immediately to prevent students from falling into educational holes.