My Spondylolisthesis Story: Braden Cousineau

April 28, 2015

In seven days, my life was turned upside down, shaken up and spun in the opposite direction. I had my post high school plan all set. I dreamed of serving in the Army since eighth grade. I was ready to start to peak in my high school track career. I was ready to play my senior season of football with the guys I had become close to over the years. I thought I was invincible like every other teenager, but that all changed with a couple x-rays, a six-inch incision and a ten-hour surgery. Welcome to my journey with Spondylolisthesis.

A normal person’s vertebrae overlap one another and fit together like a bunch of elongated “S” shapes (or tangent graphs, if you know trigonometry). Spondylolisthesis is a condition when there is a slip of one vertebrae from another. The vertebrae slip can come from one of two different things, a fracture of the vertebrae or a deformity. In my case, it was a deformity. While developing in vitro my lowest vertebrae decided to not follow the pattern of the others. Instead, the lower part of my L5 vertebrae formed behind the upper part of my S1 vertebrae. What all this means is that the lowest part of my spine had been balancing on top of my hips since birth. Since you have a natural curve in your lower spine, the Lumbar curve, the vertebrae need structural support to hang on, otherwise they slip off like a skier going down a slope. Although the slip isn’t very fast, because you have other non-bone support. Within the past 6-12 months, the vertebrae had completely slipped. For a good amount of time my upper body was free floating and I had no structural support at all. This made playing sports and doing daily activities hard, and at times excruciatingly painful.

I have always been very tight and not flexible at all, but my diagnosis explained all of this. Because of the way my body had compensated, I had a lot of problems. Over the recent years, I had become noticeably slower and much weaker in my lower body. This is one way my body compensated for no structural support. At the time of my surgery, I couldn’t bend over and touch my knees without feeling like my hamstrings were going to pop. The doctors told me that because of the way my hips repositioned themselves, my hamstrings were under constant tension. What the normal person feels when they touch their toes is what my hamstrings endured 24/7.

My legs have never been very strong, so the weakness in my legs at first wasn’t very surprising; I don’t come from a family of very strong and athletic people. My mom’s side is tall and skinny and my dad’s side is short. I just figured that I got the short straw and was screwed by the gene pool. Although this is partially true, it didn’t really add up. In the winter of my freshman year, I was able to squat about 250 pounds. By the winter of my junior year, I was lucky to hit 180 pounds, and I felt like that weight was going to crush me down into an accordion shape, like you see in the cartoons. Now that difference may be understandable if I had stopped working out, but it was the exact opposite. In the winter of my freshman year, I worked out when I felt like it, but since summer of my sophomore year, I had been on a regular workout program.

By the time sophomore year rolled around, I had come to accept that I wasn’t even close to being very athletic. Over the years of running 40-yard dashes for football, I was happy if I beat the average lineman that was carrying about twice my body weight. In the summer before my junior year, I was able to beat almost all of the linemen (not to pick on any of them, but they aren’t seen as the fastest breed out there). By the winter of my junior year, right before my surgery I couldn’t beat even the slowest ones. I had declined so fast in everything I was doing and didn’t have a clue as to why.

One day after doing a running workout for football I was having abnormal hamstring pains, so I decided to go see the trainer. She had me try to touch my toes, so I bent over and touched my knees.

She said, “Let me take a picture and show you something.”

My spine had a very noticeable curve and my hips were at two different levels. Little did I know that that discovery would turn my life upside down. I went home and told my parents about the trainer’s discovery and within the next couple weeks, I was at my doctor’s office to find out how to correct the scoliosis (curve in the spine).

My doctor walked in the room and started to check me out and had me do all these weird tests like walking on my heels and toes. She was absolutely stumped; she had seen scoliosis like any other pediatric doctor, but nothing with my kind of symptoms. She sent us to a couple different hospitals for x-rays and a leg discrepancy test (x-ray measurement of my legs and comparing them). One of our family friends is a recently retired Army nurse, he seemed to think that one of my femurs was growing faster than the other. This was the only thing that seemed to make sense at that point.

We were at the University of Minnesota a few days a later for the leg discrepancy test. The leg expert was going over the x-ray with my mom and me, and told us that my legs were the same length. We were completely confused. How does your body distort so badly with no cause? The leg expert had something to say to this, “Come with me, we are going to take one more x-ray.”

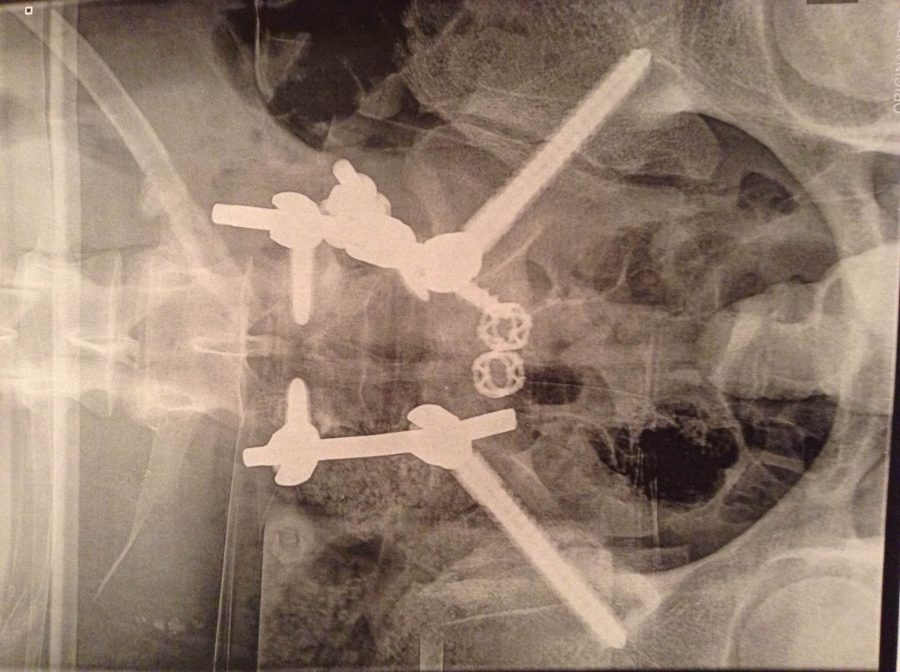

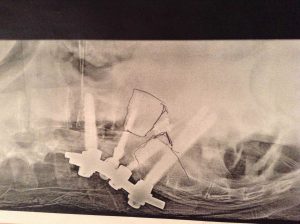

Up to this point, I had only had x-rays taken from my back side. I now had a side view x-ray taken, and we could see clearly that my L5 vertebrae was actually lower than my S1 rather than being stacked on top of the S1. The doctor told me that it was called Spondylolisthesis.

A day or two later, we were back at the U of M for a MRI. This required sitting still for 30 minutes in a tube not much bigger than my body. Since I couldn’t sit in the same position for 10 minutes without pain, I hated the MRI. When you go in for a MRI, you lay you down on a bench and put on these huge headphones. These are used so they can communicate with you when they slide you into the tube and to play music. If you ask me, the music is pointless because you can’t hear it over the noises of the machine. They slid me into the tube, and it wasn’t even two minutes before the nurse started talking to me though the headphones. I thought it was hilarious when she asked, “Braden, could you lay a bit straighter for me?” I laughed and said I was laying as straight as I could. She continued, “Well honey, could you try a little bit harder for me? The machine is telling me that you are crooked in there.” It took me a second before I realized that they probably didn’t tell her why I was having this test. I had to try to explain that I was laying as straight as I could, the scoliosis made it look like I was laying cockeyed. When we got the MRI image back, we saw that the disk between my L5 and S1 looked like it went through a meat grinder.

Before I went into see the leg specialist, I thought it would be a quick fix with some therapy. I was still thinking I’m just abnormally tight and everything would be just fine. Six days later, I was sitting in the office of a spine specialist at the U of M and had no idea that he was going to throw me for a loop.

“Braden, you are going to need a spinal fusion surgery to fuse L4 to S1. If you don’t, you will be paralyzed from the waist down within the next 10 years.”

At that point, I wasn’t too taken aback. I knew I was messed up, all I wanted was to be normal. Since the surgery was going to be soon, I knew I was going to miss track season. I was disappointed because I wouldn’t be able to pole vault and I wasn’t going to compete with the great jumpers that I had been with for the last few years, as they will graduate at the end of the year. The three of us were in a good position to sweep most of our varsity meets. I was able to deal with this because I figured all I was losing was one year of track. I had no idea that this was just the first of my losses.

A little while after this doctor visit, I stared to look in depth about medical standards for the Army. I had been planning for a few years to contact with the Army and earn a commission as an officer through an ROTC program. The medical standards say that they won’t even look at you if you currently have, or have had a history with Spondylolisthesis, or have any kind of metal in you. They don’t like metal in you unless it’s put there by them, and that usually isn’t from a pre-existing injury. This was the first punch of a wicked one-two that Spondylolisthesis was going to land on me. I now had to restructure my life plan.

The next step was to have an appointment at which the doctors were going to give my parents and me the rundown of the surgery. When we got there, we found out that my case had been handed over to the head of the spinal branch of the hospital, Dr. David Polly. My case went to him because it was so rare. They only get a condition like mine once every year to year and a half at the hospital, and there are around 100-150 of these cases across the United States every year. We found out that it would be an eight-hour procedure and it was incredibly high-risk. I would have a 20-30 percent chance of losing the ability to move my left foot up and to the right. That was only one of the many things that could go wrong. The weirdest thing is that years ago, they didn’t have this procedure, people that had this had to do physical therapy to help control symptoms, and wait for the day that they couldn’t walk again.

The worst part of this was the second punch of the one-two. I won’t be able to play football my senior year or ever again. They said it is too high-risk. Most people don’t understand how big this is for me. After high school, you can play basketball with ease, the same with baseball, soccer or most every sport. Unless you are fortunate to play collegiate football, you’re done. It’s over.

When people ask me about football and how important it is to me, I always tell them that it is my second religion. On Sundays, I go to church and come home to watch football. My dad has coached football since my brother was in fourth grade. He’s had a job as a high school coach for as long as I can remember. I was brought up breathing football. As a kid, I wouldn’t wake up and turn on cartoons, I turned on Sports Center. I couldn’t get enough of it. My brother and I were always running around and beating on each other, most of the time it came in the form of football.

Football is one of the only sports where it is encouraged to beat the man in front of you with maximum aggression. If I did that anywhere else, I would get in major trouble with the law. I believe that the bond that I have with my football teammates is one of the strongest I could have with a group of people. Football is a huge part of my life and now my last chance to play is gone. People always tell you to play every play like it’s your last, because you don’t know when it will be over, they are absolutely right. I’d do a lot to play one more game. That knocked me down for the count. And to further pour salt in the wound, the doctor told me that pole vaulting next year is a maybe.

At that point, I didn’t care what they did to me, as long as they fixed me so I could go back to normal. I would have chosen to have the surgery the next day if I could. We were planning to have the surgery on Friday, March 13. Dr. Polly had a big doctor conference that day, so we had to do it earlier if I was going to be presented at the upcoming spine conference. Yes, I am now a textbook lesson for medical students. We ended up scheduling for Monday, March 9.

The morning of the ninth, I had to wake up at 4 a.m. We had to be at the U of M Children’s Hospital before 7:30 for pre op. Most people wouldn’t be excited for the procedure, but I was. I was excited for it to happen so I could get back to normal. I also found everything really interesting.

My day started with a shower with a body wash that was the consistency of water and was made up of 3 percent of some kind of acid. I named the stuff “Satan’s Saliva,” because of what it felt like on my skin. I had to take a shower with it the night before, too. It had an acid burn kind of feeling, and I had to use a whole bottle of the stuff from head to toes between the two showers.

Pre op was pretty straight forward. They brought me into a room and had me change into a gown. The nurse came in and did a final cleansing of the part of my back that they were going to make the incision on with more acid stuff. She took all kinds of vitals, which I would become very familiar with over the next week. After she was done, my parents were allowed to come in, and all of the people on my surgery team stopped in and said hello.

The surgeon’s assistant came in and explained the whole procedure. This was the basic run down: they were going to go in and put my spine back in where it should be, rotate my hips back to where they should be and bolt it all into place. The only part that freaked me out was that I would have a breathing tube and a catheter in when I woke up. The last person to come in for pre op was the anesthesiologist. He took a bit of blood from me and started my fluids line. The needle was so big that you could see the opening on the tip. He put some numbing medication in my arm so I wouldn’t feel it go in. Once he got it in, he gave me my “breakfast in a syringe,” since I hadn’t been able to eat since midnight.

As the nutrients went in the anesthesiologist asked, “How does your breakfast taste?”

After my fluid line was all set to go, I said goodbye to my parents and a couple of nurses wheeled me to the operating room. I remember being wheeled in there and seeing about 10-15 people bustling around, yelling stuff out. There were these huge silver lights above the operating table. A guy came up behind me and put a mask on me that looked like one that you see on a CPAP machine. He told me to take a few deep breaths, I took one and remember thinking about how it smelled really bad. I don’t remember my second.

The procedure ended up being 10 hours instead of the planned eight. During the procedure, they had a machine that was like a GPS system for all of my nerves. They would constantly check on my nerves with it. At the end of eight hours they thought they had finished. They got my spine completely back on and had all the hardware in. They checked my nerves with the machine and the left side of my body was paralyzed. They had to go back in and push my spine about halfway back where it came from and remove a little hardware on my left side. It isn’t a very big deal that my body wouldn’t allow my spine to be all the way back in place, because it was all bolted down and wasn’t going to move anywhere. The only part that is disappointing is that I probably would have gained three-and-a-half inches in height instead of two-and-a-half. After the repositioning, they stitched me up and moved me to the ICU. I do not remember the four days following the procedure, because I was on so many drugs.

From the pictures I saw, I looked like I got hit by a truck when I first woke up after surgery. I had a huge red mark across my forehead, huge “C” shaped marks on both of my hips and a fat lip that made it look like I took a punch to the mouth. That was the aftermath of laying face down on a metal table for 10 hours.

According to my family and the nurses, I was a pretty entertaining patient. I talked to my IV pole and thought it was my dad. I did that for most of my ICU stay. I would start talking to it and all the sudden get really confused and look at it, then stop. All I remember is looking over my shoulder and being really confused. Some of the other highlighted things that I did were offer a nurse cocaine and called one of my male nurses an obscene name. He is now referred to as the name I gave him by everyone in ICU.

Because of the trauma that my body endured, the new position it was in, and the foreign objects that were there, my body spasmed in protest for the first part of the week. These spasms were nothing compared to when someone cramps up in sports. These started in my hip area where the bolt is located. Within a few seconds, it spread down my whole leg. After a while my whole body convulsed. My mom said that even my jaw was chattering like I was extremely cold. These spasms would last about 20 minutes, 30 at their worst. It was the worst pain I have ever felt in my life. Usually a hospital is pretty quiet, when I was having a spasm the whole floor of the hospital knew. I remember a few times in particular where I was screaming so loud that it would hurt to yell. After the spasms, I would be out for a while because they took so much energy out of me. A family friend who visited in the hospital is a homicide detective and sees all kinds of messed up things every day, and he had to leave the room because he couldn’t watch one of them.

I can recall a horrible spasm that happened when Coach Beau LaBore and Coach Mark Elmer from the football team came to visit. I remember having people trying to hold me down and I was screaming at the top of my lungs for the nurse to hurry up and put drugs down my IV line to knock me out. The problem was that before the nurse could give me anything they have to scan my wrist band and log it into the computer. All I could think about was when are they going to put me out.

The nurses were my friends because they could give me drugs to relieve my spasms and pain. I met my favorite nurse in ICU on my first night. He is the nurse I nicknamed an obscene name. He wanted me to roll over right after I had a spasm. I said there wasn’t the slightest chance that I was going to let this _____ roll me over after a spasm. The nurse’s real name was Nick. Nick was by far the best nurse I had during the whole stay. He came to visit me before and after his shifts even when I moved out of the ICU. One night when I went into a spasm, Nick happened to be coming to visit me and heard me screaming when he got onto my floor. He came running down into my room and helped me breathe it out.

When it was all over, he got my attention and said, “Hey baby doll, you scream like a girl!” That is all I remembered before I crashed. I guess I deserved being called that it after what I called him.

Soon after, I was brought up to the room that I would finish out my stay at the hospital in. When I got there I was still on a large dosage of medication, so I was still a little out of it. The people that came and visited got a good laugh and some cheap entertainment. I don’t remember much until I was on a lower dose of the medication. One thing I do remember was that texting was an absolute nightmare. On one occasion, I spent just under an hour trying to send one text message because I was determined and wouldn’t let my mom help. The worst part was is that it sounded like a two year old was talking and made no sense what so ever. After that Skype became my new best friend.

The nights were not very restful, nurses were in every two hours doing vital checks. Eventually, I got used to them and was able to practically sleep through them. One morning in particular I woke up with a gauze pad taped to the crook of my elbow, the lab people came in during the night and took a blood sample from me while I was sleeping and I had no idea. I guess a major surgery helps you get used to needles pretty fast. My record for IV’s was three in each arm at the same time.

After a certain point in the week, the physical therapist was in the room twice a day. It took three days before I was able to stand up pain free. The rest of my stay was determined by when I could walk a considerable distance and make it up and down the amount of stairs in my house.

Needless to say, the recovery process has been and will continue to be long and tough. I was out of school for six weeks, which was a very rough process. By the time I started doing schoolwork I was about three weeks behind. My work overlapped into school when I got back, so I will be doing double the work for a while. My activity level will be minimal for at least six months.

In the end, looking back over everything I have learned a lot. I learned that you cannot take anything for granted because it could all be gone in a blink of an eye. One other thing that I have learned is that you have to play with the hand you are dealt. One thing that I got asked a lot was, “How are you not really mad about this?” Some people would say that they are terribly sorry that this happened to me, or that bad things shouldn’t have to happen to good people. To all of that I say that this: No, I am not mad that this happened to me. Whatever I was planning on doing with my life must not have been what I was meant to do. I think that the worst thing someone can do is wallow in self-pity over something they cannot change. I get that what happened to me wasn’t terminal and it may be easy for me to say, but I think that it is pointless to sit and mope around and say “poor me” in every situation. If you can’t change your situation, make the most out of what you have.

Another thing that I learned in the hospital was that there are always people dealing with bigger challenges than you. The floor that I was on was on during my stay at the hospital was the bone marrow transplant floor. That floor was overflow for the spine floor due to renovations. Just rooms away there were little kids that had life-threatening problems that were incredibly hard to fix. The worst that could happen to me was I would be paralyzed from the hips down, these kids could die.

The first time walked down the hall for physical therapy, there was this woman in the hall. I was using a walker and gimping down the hall. I looked like I got hit by a bus and was coming back to my room ready to crash on my bed. This woman saw me and started cheering and dancing for me, I had no idea who she was. I came to find out that this woman was the mother of one of the bone marrow transplant patients. Her son was 18 and he had been in and out of the hospital since he was born. He spent more time in 18 years at the hospital than in his home. I was only there for a week and I was ready to go. There is always someone with bigger challenges than you.

The afternoon that I left the hospital I was excited to be going home, I got up and was looking out my window. From my view you could see a little park for kids. Looking down to the park you could see this little girl, probably not much older than five or six years old, playing at the park. This girl was hooked up to this double IV pole that had so many lines coming from it full of medicine and wires coming from the machines on top of it that you couldn’t count them. Her dad was wheeling the IV poles along behind his daughter while she went around the park. Her mom picked her up and was putting her halfway up the slide and helping her slide down. The little girl looked so happy to just be outside. A little while later, I went in for my final x-ray, when I got back to my floor I saw this little girl. She had lines and wires attached to her, an oxygen tank and a shaven head, but she looked so happy. Some kids her age are able to go to school, have play dates with their friends and live a normal life. This little girl couldn’t, but she looked happier than any other kid I had seen in a while. I went back to my room in a wheelchair and was able to leave the hospital to go home soon after.

I insisted on walking out of the hospital but the nurse and my mom wouldn’t allow me to walk anywhere past the floor I was on. As I got down to the hallway at the end of my floor, I saw a metal plate on the wall at eye level that said “Zach Sobiech Osteosarcoma Fund” on it. One final reminder to me that there isn’t any reason for me to pity myself.

My whole point is that it could always be worse, there isn’t any room for self-pity. In all walks of life, there are always worse situations than the one you are in. There are moms dancing in celebration for strangers that are doing well in therapy while their son is in the next room fighting a lifelong battle for his life. There are little girls that are ecstatic just to even set foot outdoors, because they are stuck in a hospital bed all the time. There are families that have lost loved ones to terminal illnesses. My experience with Spondylolisthesis has taught me to not sweat the small stuff, because there isn’t time or reason for self-pity. Play with what you’re dealt, and when times get tough, remember someone is going through hell compared to you.

When everything is all said and done, I am glad that I went through all of this. The process taught me a lot of lessons that I will remember for a long time. I am fixed and ready to take on a new journey with the things that I have learned.

parkeoli000 • May 28, 2015 at 10:25 pm

Really inspirational story man! You killed it, glad you got to write this by yourself. Nice to see you healthy back in school and the weightroom! Its hard to not appreciate what you have after reading this.

Megan Friederichs • May 14, 2015 at 5:15 pm

The story is so touching at the end you made me really think and appreciate everything i have. So good, you wrote it really well, worth the read

Dan Justesen • May 12, 2015 at 8:43 pm

Worth the read! It is a great story and Braden put a ton of great work into this article! Such great detail and an amazing job of explaining everything! This article is probably as good as any professional sports article! Plus it has a lot inspiring words that pulls the entire article together! Wonderful article